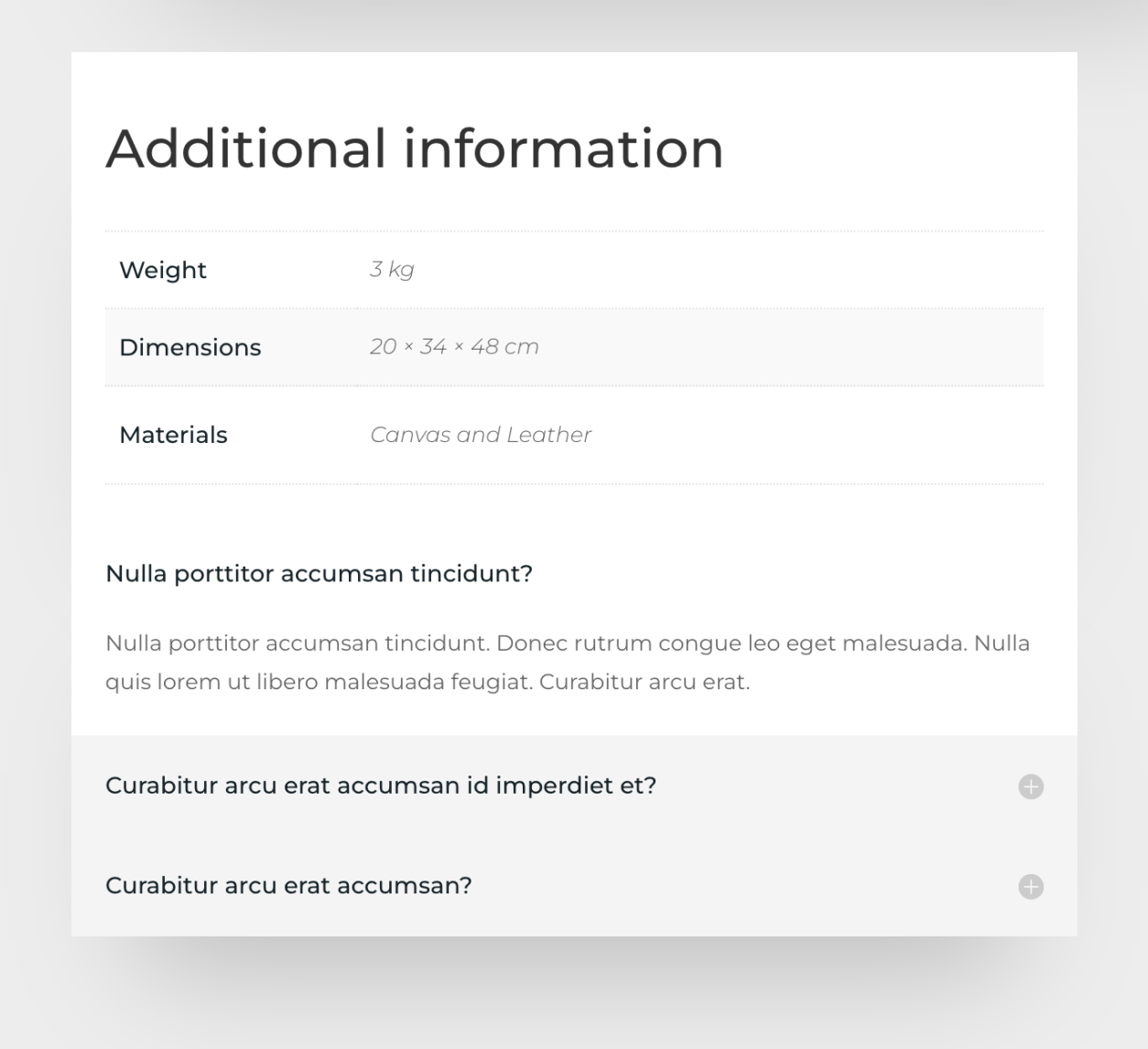

WooCommerce Product Information

Divi Module by Elegant Themes

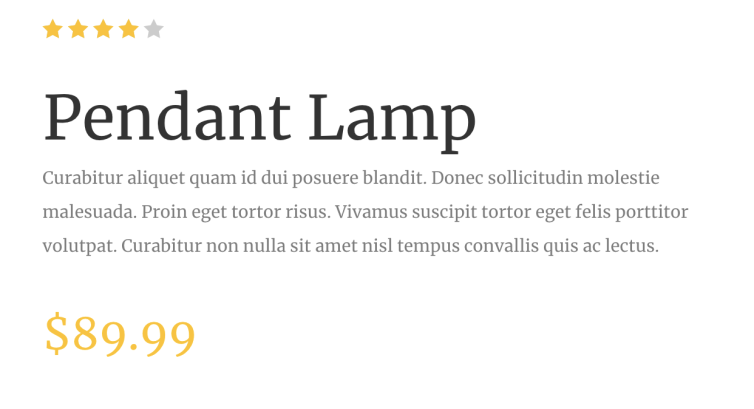

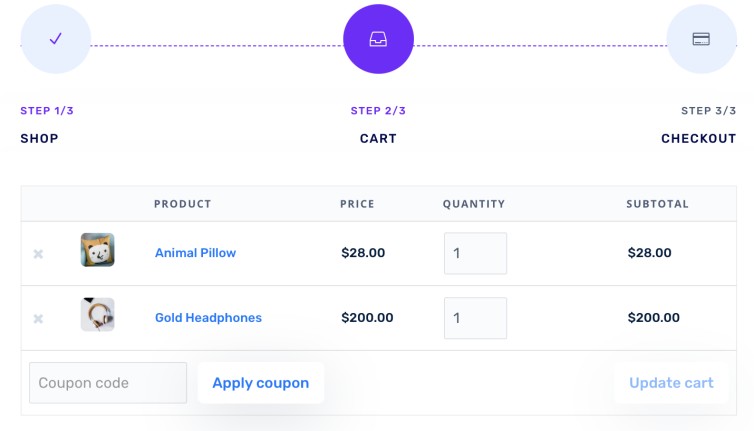

The WooCommerce product information module allows you to add the WooCommerce product additional info element of any product anywhere on your Divi site. The additional information element is based on the information given to a product including weight, dimensions, or attributes. And, with the module’s built-in design settings, you can design the product additional information with ease.

Module Documentation

How To Use The WooCommerce Product Information Module

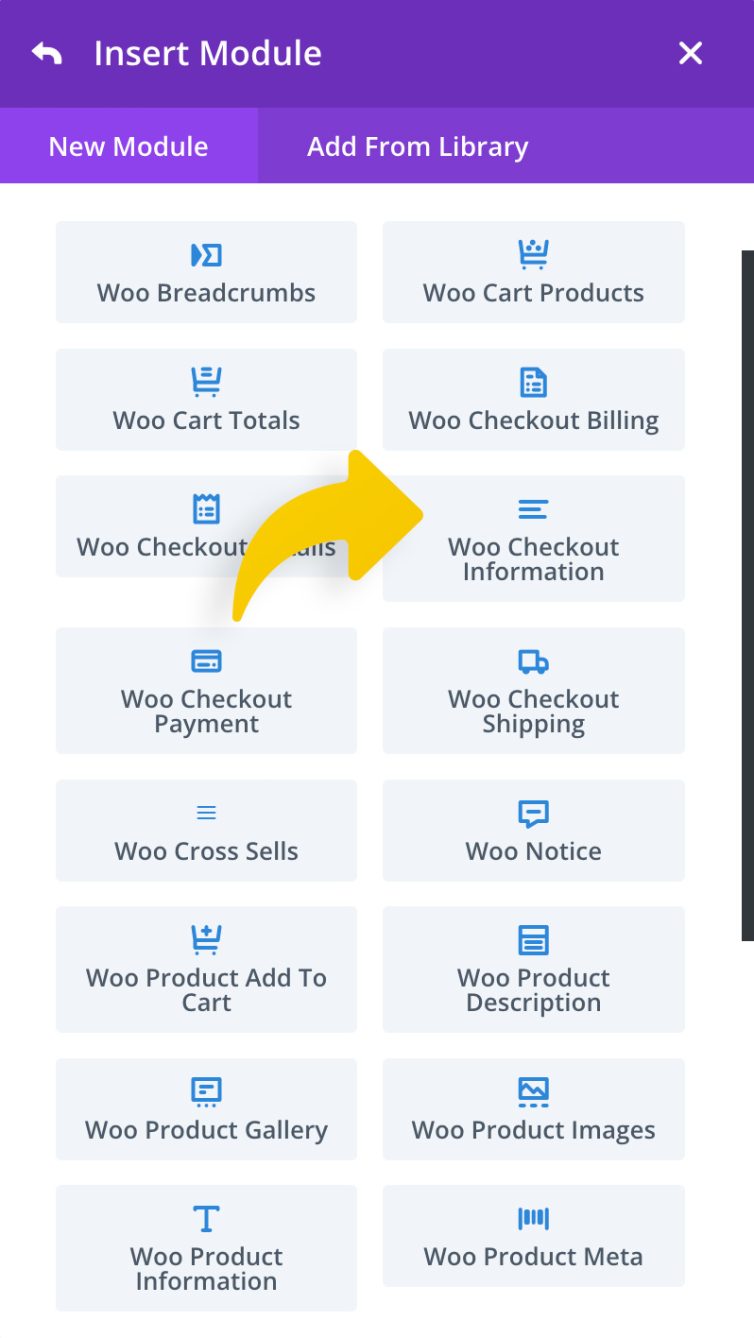

This is a native module that comes with Divi for free. To add this module to your page, simply select the WooCommerce Product Information module from Divi's module list. This module can then be fully customized using Divi's wide range of design settings.

View Module Documentation

Frequently Asked Questions

-

What is a Divi module?

Divi modules are content elements that you can use to build pages in Divi. Each module has a unique set of features, elements and design settings that help you create something unique. Different modules serve different purposes. Using Divi's huge set of modules, you can build just about any type of website.

-

Is this module included free with my Divi membership?

Yes, this is a standard Divi modules that comes with Divi. Every module built by Elegant Themes is available for free as part of your Divi membership. If you are looking for even more modules, you can browse the Divi Marketplace, which is full of both free and commercial modules developed by the community.

-

Where can I find more Divi modules?

Thanks to Divi's thriving development community, there are lots of third party Divi modules available for free and for purchase. The best place to find more Divi modules is in the Divi Marketplace.

-

How can I make my own Divi modules?

Yes, Divi's module API makes it easy for developer to create their own modules! Once you build a module, you can use it on all of your future projects or even sell it in the Divi Marketplace. To learn more about how to create your own modules, please visit our developer documentation.

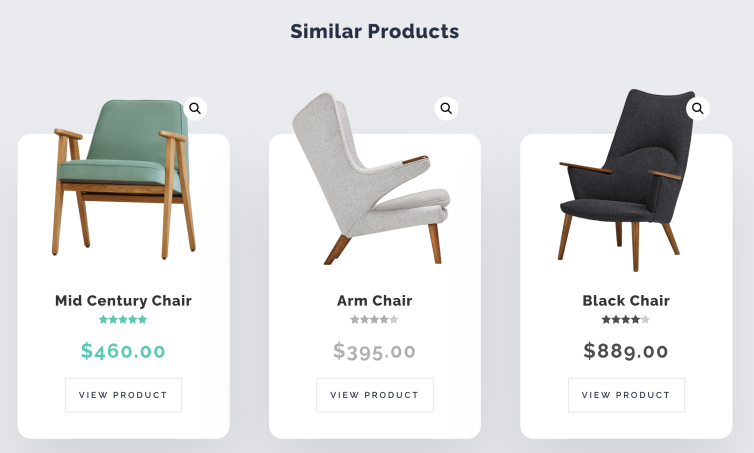

Explore More Native Divi Modules

Divi ships with dozens of native content elements that you can use to build just about any type of website. Each content element is fully customizable and includes hundreds of design settings.