Fibreglass Pools Bundaberg

Bundaberg Pool Builder

Fibreglass Pools Bundaberg

Bundaberg Pool Builder

Click Here To Apply Now!

Our team here at The Fibreglass Pool Company in Bundaberg consists of highly skilled pool builders. We have over 30 years’ experience and in that time, we have fitted and installed thousands of award-winning pools throughout the Bundaberg region.

We have a huge selection of pools to choose from, whether you are looking for a large pool to entertain the whole family, a lap pool to work on your fitness goals, or perhaps even a plunge pool or spa to relax in, you can be sure that our friendly team will help you find the pool that will enhance your backyard and lifestyle perfectly.

Our fibreglass pools surpass Australian and worldwide standards for thickness, and they are the only fibreglass shell on the market with the Australian Standards 5 Tick Certified Product Certification. When you build a pool with us, you are getting the highest quality pool that money can buy. If you would like to discuss one of our fibreglass pools for your home, call us today to organise your obligation free onsite quote.

Fibreglass pools are durable and require less maintenance than traditional concrete pools. They also come in different colors and shapes, which makes them more attractive to homeowners.

The cost of installing a fibreglass pool depends on factors such as size, shape, design, location etc. Generally speaking, you can expect to pay between $30-$80K for an inground pool made from fibreglass material. However, some pools can go over $80k due to upgrades and optional water features.

Yes! Fibreglass swimming pools have smooth surfaces and lack nooks or crannies that can trap dirt or debris. This makes them easier to clean compared with other types of pools such as concrete or even vinyl liner ones.

View Our Award Winning Range

There is no better way to enjoy leisure time at home than with an inground swimming pool or spa. Make the most of family life, relaxing, entertaining, and keeping cool on hot summer days in and around a swimming pool or spa pool.

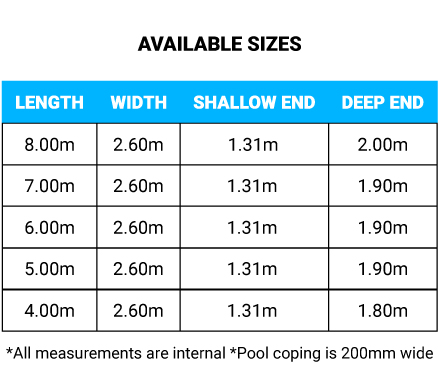

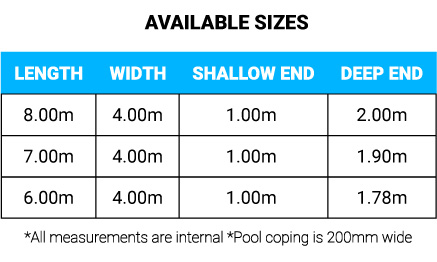

Compact yet extremely versatile, sleek and modern, the Heron newest addition to the already extensive The Fibreglass Pool Company range. The Heron is perfect for narrow backyards or restricted areas, the series features a full-length bench with dual access points, whilst still providing plenty of swimming space for the family.

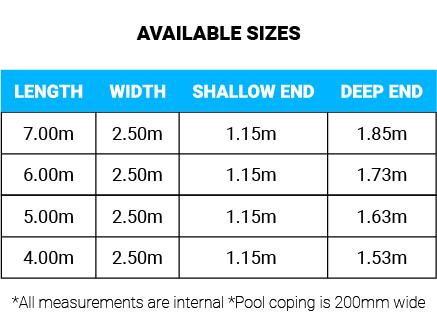

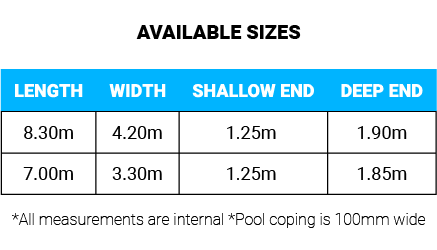

The Stradbroke Series is a slimline pool design that is perfect for narrow backyards. Designed to look sleek and fab, this pool will leave you wanting to stay in it forever. With a large selection of size ranges, you know that we have something to fit your needs.

The Hamilton series is clean and stylish, designed with a generous swimming space and spacious seating area. Perfect for those lazy afternoons for basking in the sun.

The Hamilton Slimline series has been designed with one purpose. To optimise your backyard while not taking up too much space. Offering plenty of width and generous swimming space perfect for exercise and recreation, while the full length bench seating is ideal for relaxing with family and friends. It is ideal for a dual entertaining area for the family as well.

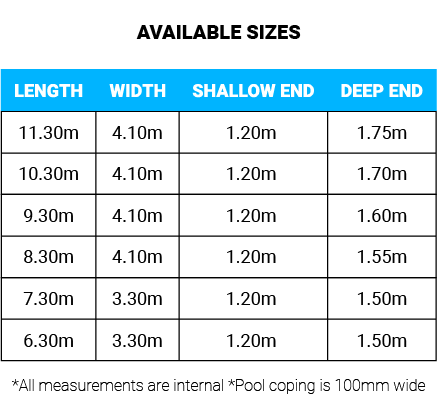

The Hampton series is one of our most popular geometric pool designs, featuring tight radius corners allowing for a clean, stylish look. The Hampton offers plenty of width and a generous swimming area, perfect for entertaining with family and friends. With plenty of space to swim in, and lounge around, who could say no to that?

The Hampton Grande features tight radius corners allowing for a clean, stylish look. With a much larger size range than its ‘Hampton’ counterpart, rest assured that if backyard space is an issue, it won’t be with this range.

The Coral Bay Series is one of our most recent additions to The Fibreglass Pool Company range. This modern pool excels and features a square internal wall showcasing the latest in design aesthetics. This magnificent one piece pool, armed with a spa combo can be run at the same time as the other, or as a pool and spa separately. It’s great for multifunctionality and perfect for the family!

The Whitehaven Series is The Fibreglass Pool Company’s latest pool release! It’s modern, sleek and complete with a built in spa – so you get the best of both worlds. Enjoy the extensive swimming space and spa section. This is a perfect pool for the whole family!

The Cottesloe is one of The Fibreglass Pool Company’s latest pool ranges. It has dual entry and exit points, allowing you to position it in a variety of ways to suit your backyard space. Bench seating runs along the full length of the pool to allow for ease of access and ultimate relaxation. It is the perfect addition to your home, or perhaps something to add in the building stages. Whatever the case, the Cottesloe is definitely worth checking out!

The Medina is a stylish pool design that is perfect for modern homes. Designed with symmetrical steps leading into the main swimming area, it is the perfect addition to your developing house or already established home.

The Riverina Series is a clean and stylish pool design. This pool offers plenty of width and generous swimming space. With curvy corners for a more playful feel to it, this is the ideal pool for the family. With a safety step around the whole pool for the little ones, there is no doubt that you will never be out of weekend activities.

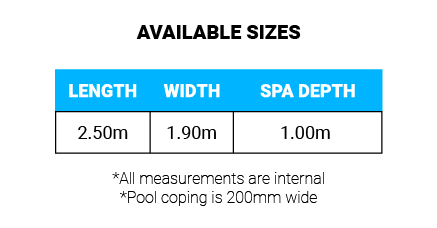

Our 2.5m x 1.9m Spa is the perfect addition to complement any pool or out-door entertainment area. Fitting up to 9 people, the spa is ideal for socialising and entertainment. Our Spas have the option to be heated separately to the pool. Perfect for hot summer days or chilly winter nights. Enjoy the best of both worlds with this one.

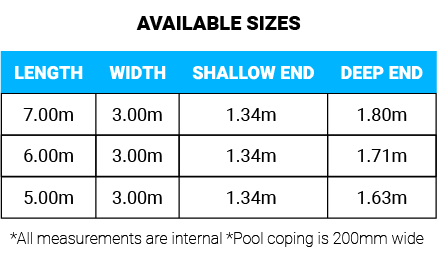

Compact yet extremely versatile, sleek and modern, the Heron newest addition to the already extensive The Fibreglass Pool Company range. The Heron is perfect for narrow backyards or restricted areas, the series features a full-length bench with dual access points, whilst still providing plenty of swimming space for the family.

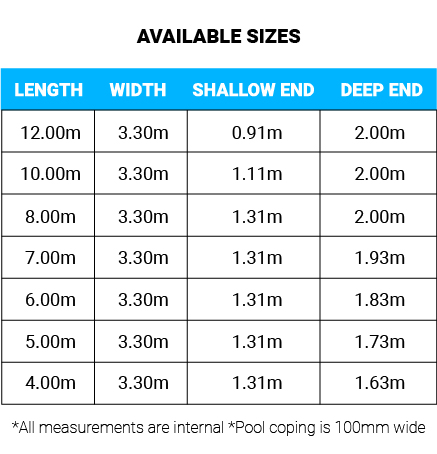

The Stradbroke Series is a slimline pool design that is perfect for narrow backyards. Designed to look sleek and fab, this pool will leave you wanting to stay in it forever. With a large selection of size ranges, you know that we have something to fit your needs.

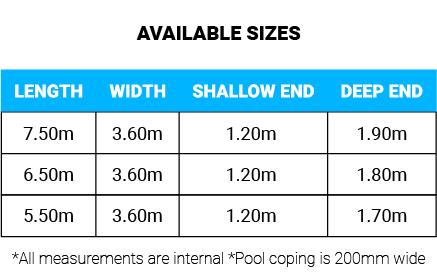

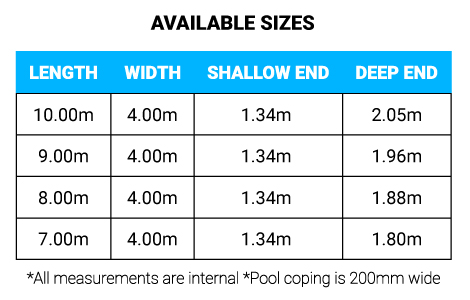

The Hamilton series is clean and stylish, designed with a generous swimming space and spacious seating area. Perfect for those lazy afternoons for basking in the sun.

The Hamilton Slimline series has been designed with one purpose. To optimise your backyard while not taking up too much space. Offering plenty of width and generous swimming space perfect for exercise and recreation, while the full length bench seating is ideal for relaxing with family and friends. It is ideal for a dual entertaining area for the family as well.

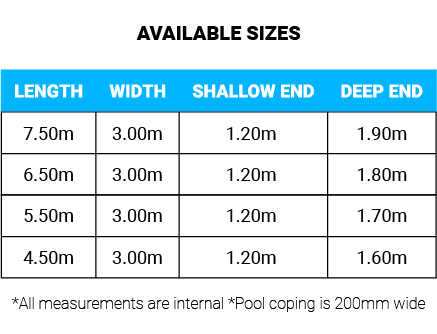

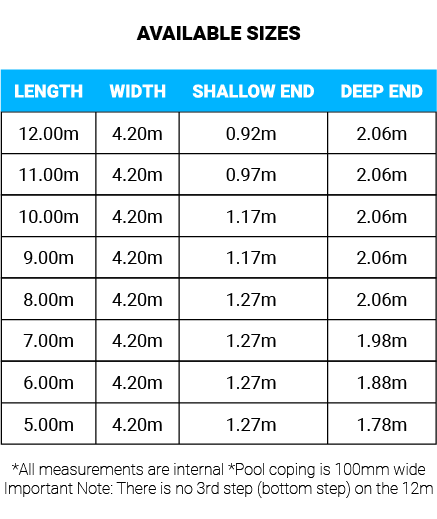

The Hampton series is one of our most popular geometric pool designs, featuring tight radius corners allowing for a clean, stylish look. The Hampton offers plenty of width and a generous swimming area, perfect for entertaining with family and friends. With plenty of space to swim in, and lounge around, who could say no to that?

The Hampton Grande features tight radius corners allowing for a clean, stylish look. With a much larger size range than its ‘Hampton’ counterpart, rest assured that if backyard space is an issue, it won’t be with this range.

The Coral Bay Series is one of our most recent additions to The Fibreglass Pool Company range. This modern pool excels and features a square internal wall showcasing the latest in design aesthetics. This magnificent one piece pool, armed with a spa combo can be run at the same time as the other, or as a pool and spa separately. It’s great for multifunctionality and perfect for the family!

The Whitehaven Series is The Fibreglass Pool Company’s latest pool release! It’s modern, sleek and complete with a built in spa – so you get the best of both worlds. Enjoy the extensive swimming space and spa section. This is a perfect pool for the whole family!

The Cottesloe is one of The Fibreglass Pool Company’s latest pool ranges. It has dual entry and exit points, allowing you to position it in a variety of ways to suit your backyard space. Bench seating runs along the full length of the pool to allow for ease of access and ultimate relaxation. It is the perfect addition to your home, or perhaps something to add in the building stages. Whatever the case, the Cottesloe is definitely worth checking out!

The Medina is a stylish pool design that is perfect for modern homes. Designed with symmetrical steps leading into the main swimming area, it is the perfect addition to your developing house or already established home.

The Riverina Series is a clean and stylish pool design. This pool offers plenty of width and generous swimming space. With curvy corners for a more playful feel to it, this is the ideal pool for the family. With a safety step around the whole pool for the little ones, there is no doubt that you will never be out of weekend activities.

Our 2.5m x 1.9m Spa is the perfect addition to complement any pool or out-door entertainment area. Fitting up to 9 people, the spa is ideal for socialising and entertainment. Our Spas have the option to be heated separately to the pool. Perfect for hot summer days or chilly winter nights. Enjoy the best of both worlds with this one.

Your Dream Pool Awaits..

Small Pools

We have a wide range of small fibreglass swimming pools, many have won SPASA awards for best inground fibreglass swimming pool, we are sure to have a pool that will suit your backyard and requirements.

Medium Pools

Our medium sized fibreglass pools are some of our most popular pool designs and are priced keenly to suit your budget. Encompassing straight lines, they look modern and up to date in any setting. With various different designs, you are spoilt for choice.

Large Pools

If you’re after size and want a swimming pool to accommodate social gatherings with friends or family, then you need to investigate our selection of sizeable inground fibreglass swimming pools. They provide that expansive, ocean feel.

9 Reasons

Why More Home Owners Choose The Fibreglass Pool Company

Have you always dreamt of being able to own your own swimming pool? Well now is the time to take the plunge as it has never been easier. The Fibreglass Pool Company are committed to providing you with a fast, easy and affordable service.

Installation

We provide a specialised installation process, when choosing a pool from the Fibreglass Pool Company it can be installed in as little as 7-10 days. All of our pools are of the highest quality and installed by our own thoroughly qualified and trained pool builders. All of our pools are steel and concrete reinforced which provides exceptional strength and longevity and all uphold a Lifetime paving guarantee.

Australian Made

The Fibreglass Pool Company has been building and installing Australia's favourite pools for the past 30 years. Our manufacturing facilities are state of the art which is why The Fibreglass Pool Company is Australia's leading Fibreglass Swimming Pools manufacturer.

Quality Control

Here at The Fibreglass Pool Company, we pride ourselves on producing only the highest quality fibreglass pools, that is why we have an 8 step quality control process. Producing the highest quality pools and exceptional workmanship is something we take seriously which is why we value our customers and want them to have a peace of mind in knowing they are buying a pool from Australia’s best Fibreglass Swimming Pool company.

Lifetime Warranties

The Fibreglass Pool Company offer an extensive and all-inclusive warranty so our customers have peace of mind in choosing one of our top-quality pools. Our warranty is Lifetime Structural, Lifetime Internal and our Lifetime Paving Warranty all fully transferable.

Construction

All of our pools come with a 7 first-class construction guarantee. Our pool colour technology is the best on the market today and comes with a lifetime interior surface guarantee. Our state of the art 7 layer Fade Resistant and Anti-Microbial construction puts us above the rest as it includes interior surface finish, anti-corrosion barrier, chemical resistant layer, kevlar, structural layer, reinforcement layer and outer sealer coat.

Certification

The Fibreglass Pool Company have invested over 10 years designing and building top quality fibreglass pools. Because of the amount of time and hard work we have dedicated into our pools, is why we have such an extensive range of fibreglass pools to choose from. We pride ourselves on delivering only the highest quality and are proud to say we are Australia’s only Fibreglass Pool Manufacturer to be awarded the Australian Standards 5 tick certified product award.

Award Winning Range

The Fibreglass Pool Company have one of Australia’s largest range of fibreglass pools to choose from. Our range is simply endless with several different sizes, colours, and styles to choose from. Our designs are exquisite with many beautiful colours and shimmer effects to choose from. Our extensive range of pools is award-winning which sets us above from the rest of the competition.

Safety & Maintenance

When it comes to safety we go above and beyond to ensure all our regulations are met. Customers can feel at ease and have peace of mind knowing that all of our fibreglass pools come with a safety step ledge around each pool, smooth non-abrasive surfaces with no sharp edges and non-skid on the step-entry and floors.

Anti Microbial

Here at The Fibreglass Pool Company all of our pools include a Gel Coat protection to help your family against harmful bacteria. Each and every one of our pools have been built with our Anti-Microbial Polycor 943 Gelcoat Protection.

4 Easy Steps To Owning Your Swimming Pool

Owning Your Own Swimming Pool Is Only 4 Steps Away!

1

Get A Free No-Obligation Quote

One of our friendly and experienced team from The Fibreglass Pool Company will be in contact to organise a quote onsite.

2

Obtaining The Approval For Your Quote

All council approvals will be organised by our experienced dealer, this will be done before we start the job.

3

Installation Of Your Pool

We will start the process of the construction and excavation of your pool, you can rest assured that this process will be hassle-free as much as possible and can take as little as 7 days to be completed.

4

Enjoying Your Pool

Congratulations you now have your own top quality fibreglass swimming pool with one of Australia’s favourite companies. Now you can enjoy those warm sunny days, relax, have fun and make the most of life for many years to come.

Enjoy the Ultimate Swimming Experience with a Fibreglass Pool from The Fibreglass Pool Company in Bundaberg

When it comes to transforming your outdoor space into a private oasis, nothing compares to the beauty, durability, and versatility of a fibreglass pool. If you’re considering adding a pool to your property in Bundaberg, look no further than The Fibreglass Pool Company. With their exceptional craftsmanship, industry expertise, and commitment to customer satisfaction, they offer the perfect solution for your swimming pool needs. In this article, we will explore the top reasons why you should choose a fibreglass pool from The Fibreglass Pool Company in Bundaberg.

Unmatched Quality and Durability:

The Fibreglass Pool Company takes pride in delivering top-quality fibreglass pools that are built to last. Their pools are constructed using advanced composite materials that are resistant to corrosion, cracking, and fading. Fibreglass pools require minimal maintenance and are less prone to leaks compared to other pool types. With a fibreglass pool from The Fibreglass Pool Company, you can enjoy years of worry-free swimming and relaxation.

Wide Range of Designs and Sizes:

Whether you have a small backyard or a spacious outdoor area, The Fibreglass Pool Company offers a diverse selection of pool designs and sizes to suit your specific requirements. From sleek and modern designs to more traditional and elegant styles, their pool range has something to complement any landscape. Choose from a variety of shapes, including rectangular, kidney, freeform, and lap pools, to create the perfect centerpiece for your outdoor space.

Quick Installation Process:

One of the key advantages of choosing a fibreglass pool is the remarkably fast installation process. The Fibreglass Pool Company utilizes advanced manufacturing techniques to produce pre-fabricated pool shells that can be swiftly installed on-site. This means you can have your dream pool up and running in a fraction of the time it takes to construct other types of pools. With their efficient installation process, you can be swimming and enjoying your pool in no time.

Excellent Energy Efficiency:

The Fibreglass Pool Company understands the importance of energy efficiency in today’s environmentally conscious world. Their fibreglass pools are designed to maximize energy savings by utilizing innovative insulation techniques. The insulating properties of fibreglass help to retain heat, reducing the need for excessive heating and saving you money on energy bills. Additionally, fibreglass pools require fewer chemicals to maintain optimal water balance, further contributing to their eco-friendly profile.

Outstanding Warranty and Customer Support:

When you choose The Fibreglass Pool Company in Bundaberg, you can have complete peace of mind knowing that your investment is protected. They offer comprehensive warranties on their fibreglass pools, including lifetime structural warranties. In addition, their dedicated team of professionals is committed to providing exceptional customer support throughout the entire pool ownership journey. From initial design consultation to after-sales service, they are there to assist you every step of the way.

Investing in a fibreglass pool from The Fibreglass Pool Company in Bundaberg is a decision that guarantees years of enjoyment, relaxation, and family fun. With their commitment to quality, extensive range of designs, quick installation process, energy efficiency, and exceptional customer support, they stand out as the premier choice for fibreglass pools in the area. Take the first step towards creating your dream outdoor space and contact The Fibreglass Pool Company today to turn your pool dreams into reality.